Last summer when I first started experimenting with The Croissant Diet I had breakfast at a friend’s place. He was on The Carnivore diet and had been inspired by Paul Saladino to eat fried beef suet with his eggs. I had a plate of eggs and beef suet and the suet was… waxy. Much more so than normal beef fat. My only prior experience with eating suet was my grandmothers suet pudding, which she made every Christmas. Maybe she had been onto something! I wasn’t ready to shout out the stearic acid content of beef suet to the world because I wanted more evidence first. Frustratingly, I couldn’t find a single paper that listed the fat composition of beef suet.

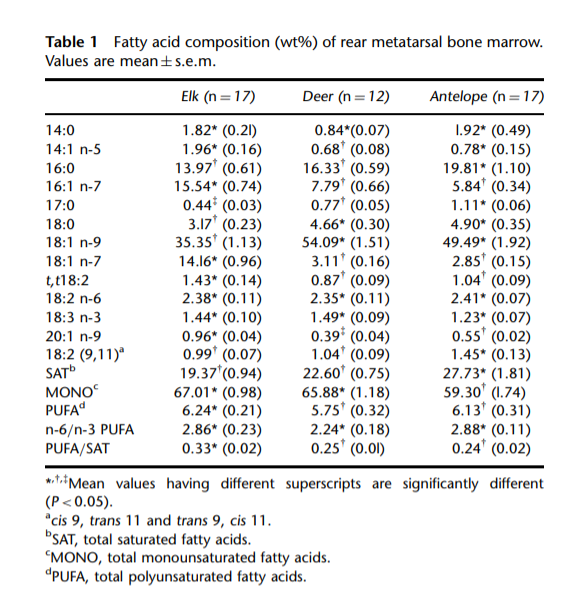

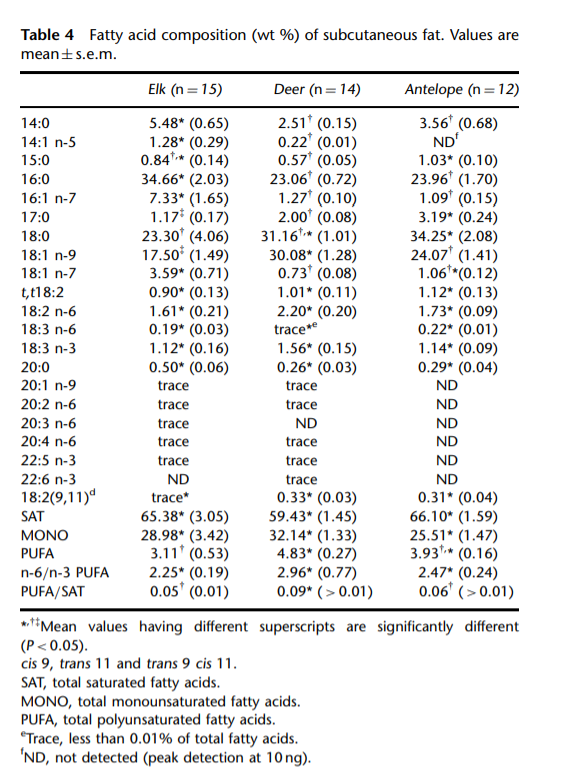

Something that is made very clear by this Cordain paper is that the fat composition of different tissues varies markedly within the same animal. For instance, the saturated fat content of wild elk bone marrow is 20% whereas the saturated fat content of wild elk backfat (subcutaneous) is 65%!

In the original Croissant Diet specification I listed wild elk backfat as one of the best sources of stearic acid as a result of this paper. Obviously it was a little tongue-in-cheek, I wasn’t expecting people to go out and start hunting elk for the backfat, but I think it’s an interesting historical perspective that shows the normal upper range of saturated fat in traditional human foods.

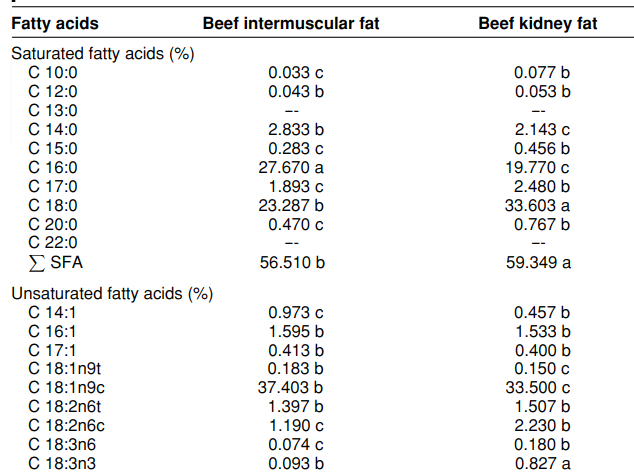

I’ve always been frustrated that this paper doesn’t report on the fat composition of abdominal fat or kidney fat – the layer of fat that surrounds the internal organs. This is the layer of fat that in a cow is called beef suet. Nor could I find the fat composition of kidney fat in any other paper, until Stefano Shiavi tweeted this:

Finally, some data! The link to the paper is here.

If this data is true, beef kidney fat would be a true stearic acid superfood, up there with cocoa butter, my stearic acid enhanced butteroil and wild elk backfat. Not only was the beef suet high in saturated fat in general but the majority of the saturated fat was from stearic acid. There are not many foods for which this is true. But I only had the one data point and this is a Turkish paper and it could be due to something specific about the breeds or feeds being used in Turkey. I had reason to be suspicious: the paper reported the saturated fat content of intermuscular fat to be 56%, whereas the USDA reports that the saturated fat from the lean part of beef cuts to be around 37-40%, whether from grain finished or grass finished beef.

Math Stuff

I wanted to test the ratios to reconfirm that beef suet was as high in long chain saturated fat as was being reported but I didn’t have the extra cash to send it in for testing and I wanted to create a repeatable test that I could use for future experiments. The basic concept was this: using the leftover 50:50 stearic acid : palmitic acid (100% long chain saturated fat) I had from the original Croissant Diet test and Macadamia Nut oil (14% SatFat, 3-4% PUFA, 80% MUFA), which they sell at the local Wegmans, I could make a series of test blocks at different ratios as an example of fats that were 60:40 SFA:MUFA, 50:50, 40:60, etc. Then I could compare the firmness of those blocks to different rendered beef fats. The PUFA content would be low and similar to that in beef fat. It would give me a baseline for how firm different fats should be at different ratios of SFA:MUFA.

Collecting and Rendering Fats

I sourced some grass finished beef suet from Windsong farm in Burdett, NY. Wegmans carries grain-finished (presumably) beef suet in the dog food section, so I got some of that. Lastly, I found a piece of beef chuck that hard a large enough piece of fat in it that I could trim it out and render the fat down.

The first step is to render the fats, which is easy if you know how. I know from experience that rendering works faster the smaller the size of the fat is. So I coarsely chopped the fats then pulsed them in my food processor.

The rendering process is not unlike slow cooking bacon until the fat cooks out and the strips get crispy. I put the chopped fat into a saucepan and add a little water in the beginning to get everything steaming. I put the pot on an induction burner set to around 350 and cover it with a lid. Within minutes, fat will start to cook out from the meat, just like bacon. Soon the whole thing will be at a rolling boil.

As the rendering process continues, the solid pieces will get smaller and their color will turn darker. The boiling will mostly stop and the amount of steam produced will be much less. It is time to strain the suet.

Testing!

Once I had rendered my three samples: grassfed beef suet, grain finished beef suet and chuck fat, it was time to start testing them. And I mean immediately because I was excited. I knew from a kitchen “experiment” from a few years back that you can dump 20 quarts of 230 degree lard over your whole arm without any serious repercussions so I wasn’t shy about dipping my fingers into the hot grease.

It’s February and I keep my house pretty cool – around 60F (that’s 16C for you Canadians, which is how I categorize people who use the metric system (Kidding!! Geeze! I get that most of the world uses the metric system (‘Merica!))) – and at that temperature the grassfed suet would wax up fairly readily on my fingertip. The grain finished beef suet would wax up a little around the edges and might have eventually waxed up on my fingertip but it was definitely a lot slower. The chuck fat didn’t wax up at all.

I poured samples of my three fats into cupcake tins and started the long wait for them to fully set. From experience I knew they wouldn’t be fully set until the next day.

In the meantime I went about making my test blocks – one each at 40%, 50% and 60% SatFat. Assuming 14% SatFat in the Macadamia Nut oil, the blends looked like this (I made 40g test blocks):

| SatFat Percentage | Stearic/Palmitic Acid | Macadamia Oil |

| 40% | 12g | 28g |

| 50% | 17g | 23g |

| 60% | 22g | 18g |

The next morning there were a couple problems. The first was that the dramatically different melting points between the stearic acid triglycerides and the macadamia nut oil triglycerides had caused the test samples to crystallize while cooling. They weren’t homogenous, you could see and feel the crystals, just like in ghee. Still, they clearly each had differing levels of hardness and therefore IMO some idea about what I was looking for as a reference.

The bigger problem was that the beef suet samples were rock hard. Brittle, homogenous, rock hard blocks. How do you determine if one rock hard lump is harder than another rock hard lump? The 60% SatFat test block was also a rock hard lump.

So I made some new samples. I made two new samples from each rendered suet, diluted one with 25% Macadamia Nut Oil and the other with 50%. So for each suet sample I had 100% suet, 75% suet and 50% suet with the balance as Macadamia Nut Oil. And I waited overnight. Again. While I waited I spent a lot of time poking at the samples. What would happen?!

How is it For Cooking?

This is important, of course. Is it waxy? How is the flavor? I did what I knew I had to do which was to immediately fry up a mountain of fish and chips.

It was really quite good. I almost finished it. Personal note: I like cocktail sauce.

Conclusions

Grassfed beef suet is VERY saturated. Vastly more saturated than fat from the chuck and significantly more so than grain finished suet. I can’t tell using this technique whether the thing that makes the grassfed suet harder than the grainfed suet is higher saturated fat or lower polyunsaturated fat, but either way, I’d call it a win for the grassfed.

The USDA database says most grain finished beef fat from the chuck is around 43% saturated and 16% stearic acid. The chuck fat sample certainly seems in line with that. Sample 6 (50:50 grassfet suet : macadamia oil) is, if anything, slightly less firm than the beef chuck fat. If we assume sample 6 is 40% saturated and that macadamia oil is 14% saturated and calculate backwards, it suggests that the grassfed suet is about 66% saturated. 66% saturated fat is the exact number from the elk and antelope subcutaneous fat in the Cordain paper, so that is in the expected range of saturated fat from ruminant fat stores. In the Turkish paper, stearic acid represented 56% of the saturated fat from beef suet, suggesting a total of as much as 37% stearic acid in the grassfed beef suet. I’m not sure the 37% number is accurate, but I am sure that grassfed beef suet is an excellent source of highly saturated fat and specifically stearic acid.

I also conclude that it’s excellent for deep frying.

If you dropped a ball bearing through a tube from a fixed height say four feet, onto a puck of fat it would leave a dent. you could fill the dent with fluid from a syringe and note the volume of the dent. this would give a qualitative assement that one could use to compare cooking fats.

This is possibly crazier than anything I would come up with on my own. Which is to say: I love it.

Great article! It makes me understand that when was eating my rendered beef trim with 2 huge pieces of suet, some months before christmas, I was losing weight and couldn’t understand why all of a sudden it had become so easy! now i know.

I am unsure as to why you were mixing in with Macadamia oil and the others? Did i miss something? what are you trying to achieve with mixing them up?

I was only mixing them with macadamia nut oil to be able to compare them. Without the oil, the suets were both hard. It was like “this one’s very hard and this ones very hard”. When I diluted them with the macadamia nut oil, it became clear which one was really harder.

Huh, this reminds me of something I noticed a few years ago when I was being stingey with deer carcass. I never tried or heard of anyone cooking the ribs and I saw plenty of meat hiding in there after I cut the back straps off, so I figured what the hell, took the sawzall out and cooked them low and slow like any pork ribs- they were fantastic, rich with a similar taste to beef short ribs. What stuck out most though was the fact that while they were amazing that night, the leftovers were like eating a candle, the same waxy texture as – all that subcutaneous fat that usually get trimmed off the carcass. Great insight, gonna make me thing about different cuts of meat for a while…

Question for you: What about palm oil, which I think you said is the palmitic acid which is the 2nd best saturated fat? Spectrum sells tubs of palm oil as “non-hydrogenated shortening”. Would it be better than butter, then? And you have coconut oil listed as having the highest “ratio”, does that make it actually best to consume, even though its stearic acid content is low?

Palm oil is interesting. Although it’s high in palmitic acid, it is also quite high in linoleic acid (9%) and mice fed palm oil get very fat. I don’t recommend it.

Coconut oil has very low low PUFA, but also chort average chain lengths. I don’t recommend it only because I don’t know how differently te body treats the different chain length fats.

Awesome write-up! I did some melting point testing some years ago on different phase change material we were evaluating for heat absorption. We basically used a small glass capillary filled with the different materials. Cocoa butter was one of them. You basically submerge it in water and gradually bring the temperature up until you see it go clear/transparent and not the temperature. Depending on the rate of recoiling, cocoa butter can for different crystal complexes that significantly alters the melting point. We can also do this on our dsc when using different rates of cooling and then reheating. I’m going to get some profiles on rendered bacon fat, subcutaneous beef fat, cocoa butter and shea butter. Should be interesting. If I can remember the name of the glass capillary melt point protocol, I’ll let you know. Thanks again for taking the time to do this.

Of course! I’ve got an upcoming article showing that in any different supermarket you can find bacon of wildly different melting points. AT least in the US you can.

Can tallow be reused after deep frying?

Yes! If it gets gunky you can run it through a coffee filter.

Brad, love the blog. Just found it and read through all the articles. I particularly liked a nugget you posted in the alternate heart disease hypothesis.

“The second thing that affected k2 levels was a change in food processing technology. It is easier to separate the butter from the cream once the cream has soured. Farm produced butter was always made from soured cream. The fermentation of the cream would have contributed significant K2 mk-7 to farm produced butter. Incidentally, you can still buy “cultured butter” in the US if you know where to look, this is equivalent to the old farm produced butter.”

Do we know what bacteria produce the k2? I found several recipes online to make butter, adding both yogurt or buttermilk to the mix, but wonder which would be best. One could also use butter cultures, which are used in the making of cheese.

Butter seems much more practical than beef tallow to get stearic acid as well. Per 100 grams, it has about half as much, but can be used at room temperature. Seems like a double win.

I do not know which bacteria make the K2. My guess is that most of them do? idk.

And thank you!

Brad

What I wonder is how do you know what you’re getting with beef fat? For instance:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B06WWG7P4Z/?coliid=I32QVMYNAQS0E6&colid=15LWHGA04FA5N&psc=1&ref_=lv_ov_lig_dp_it

Do you think this is mainly suet? Or just “fat”?

My local store now has its own version of grass fed beef. I’m going to ask them if they can get me suet. I’ll see what they say.

You may already have figured this out, but Tallow is simply rendered Suet. Theoretically what’s in that bucket from Amazon is just that, but it couldn’t hurt to try to get verification from the seller.

Any rendered beef fat can be called tallow, whether or not it is suet: kidney fat. When you butcher a cow there’s a LOT of trim other than just the suet that goes into the trim bucket. Some brands may be selling pure rendered beef suet as tallow but no one is making the claim explicitly. This is defined here by the USDA:

https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/wcm/connect/7c48be3e-e516-4ccf-a2d5-b95a128f04ae/Labeling-Policy-Book.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

“TALLOW:

Acceptable product name for the meat food product consisting of rendered beef fat or

mutton fat or both. “

Yeah, I don’t know. That’s kind of the point. Unfortunately it’s not spelled out anywhere.